ADELE FERRAND, PORTRAIT PAINTER

Adèle Ferrand, Portrait posthume de Melle Trolong, 1839

The golden age of portrait painting in France

In the 19th century, before the fashion for photography, tens of thousands of portraits were painted. The oldest of the portrait painters under the July Monarchy studied at the school of the painter David, but the most sought-after were those who had trained with Ingres.

Hundreds of other artists like Adele Ferrand painted on commission for clients form the aristocracy or bourgeoisie, who considered it fashionable to hang family portraits in the living room.

Adele Ferrand’s portraits in the Leon-Dierx art gallery are of her own family or close friends, with the exception of two paintings bought after the 1922 bequest which were painted on commission.

Adèle Ferrand, Autoportrait à la robe blanche, 2e quart 19e siècle

Self-portrait of Adele

There are two known self-portraits of Adele Ferrand. In the first, showing Adele as a young girl, her face is still chubby and framed by curly locks. She is dressed in white and is holding a red book.

The painting is particularly successful, as regards the rendering of the white cloth of the dress and its sash, the gleam of the taffeta and the vaporous quality of the muslin; in the background, a landscape with its colours softened by the sunset serves as a balance for the model’s pale face. The presence of the book asserts the importance of thought, intellect, in the creative process.

Adèle Ferrand, Autoportrait présumé ; Esquisse pour le portrait de Mme Le Coat de Kervéguen ; Autoportrait présumé, 2e quart 19e siècle

Adèle Ferrand, Portrait de Mme Ferrand (mère d'Adèle), 1849

Portrait de Mme Ferrand

C’est par le portrait de sa mère Mme Ferrand, qu’elle est remarquée par la critique au Salon à Paris en 1840 : l’œuvre était exposée dans le grand salon du Louvre au-dessus d’une porte, bien visible. Un critique écrit dans le Journal des Artistes : « C’est là un remarquable portrait bien réussi et qui révèle un grand avenir chez une toute jeune artiste… La tête, d’une bonne couleur est bien modelée, franchement peinte et surtout vivante. »

Cette femme au manchon de fourrure pose presque de face, au centre de la toile. Elle revêt une cape noire dont la capuche doublée de satin blanc, aux plis multiples peints avec brio, encadre le visage d’une femme mûre mais paisible. L’artiste a cherché à rompre la symétrie en ne dévoilant qu’une longue main, froissant un gant de cuir clair tandis qu’un ruban rouge ponctue le bord inférieur de la toile. Cette touche vive rompt avec l’harmonie de gris, de noir et de brun qui renforce le caractère hivernal du portrait.

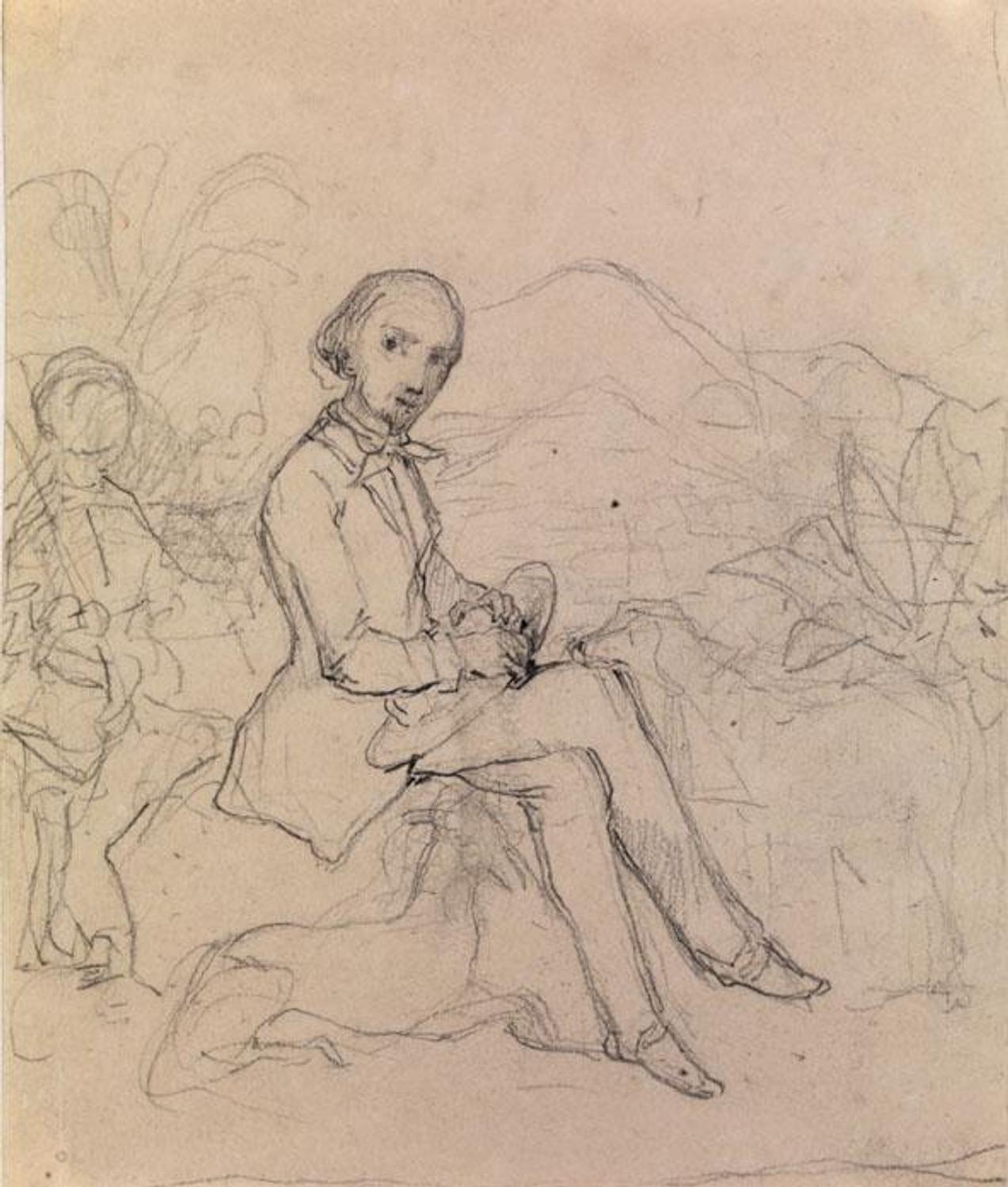

Adèle Ferrand, Portrait de Denis François Le Coat de Kervéguen, vers 1845-1846

Denis François Le Coat de Kervéguen

When Adele arrived in Reunion with her family at the end of 1846, she painted portraits of her family and close friends, as well as a few on commission.

The portrait of her husband Denis François Le Coat de Kerveguen represents a man sitting in a cosy drawing room with a dog at his side. The painting vaguely recalls the small portrait of a trader painted by Arie de Vois, that Adele had made of sketch of in the Louvre. The painting hanging on the wall, the books, the maps, the globe and the sheet music on the table: everything points to the sitter being a well-educated member of the bourgeoisie and sensitive to the arts.

Adèle Ferrand, Portrait présumé de Denis François Le Coat de Kervéguen et son chien ; 2e quart 19e siècle; Esquisse pour le portrait de Denis François Le Coat de Kervéguen, 1847 ; Portrait d'un jeune homme, 2e quart 19e siècle.

Adèle Ferrand, Portrait présumé de Geneviève Hortense Le Coat de Kervéguen, 1848

Portrait of Mme de Kerveguen

The supposed portrait of Genevieve Hortense de Kerveguen, the artist’s mother-in-law, is a perfectly skilful work of art.

Madame de Kerveguen, sitting on a red sofa with her arms crossed, is presented slightly sideways and a little off-centre. The tassels on the cushion and the gilded studs on the back of the sofa echo the tawny-coloured brocade at the back. This fabric, a symbol of wealth, evokes the drapes visible in certain of Van Dyck’s portraits that Adele Ferrand copied in the Louvre. The black fabric of her dress, the shawl, also black, lined with red, are skilfully painted, the light playing on the folds giving the model a certain solidity. A fan, as well as her lace cuffs and collar with its large white bow, highlight the portrait as a whole.

All of these discrete signs of bourgeois opulence contrast with the model’s strained tired features, expressing deep sadness.